Featured in New City Magazine (Part 1 of 6)

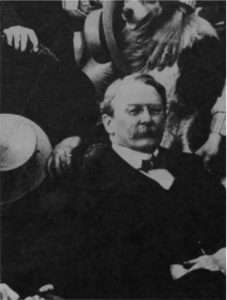

Ralph Clarkson in his Fine Arts Building studio, 1924/courtesy Chicago History Museum

Act One of a ten-part series.

Read the Intro here with links to the entire series.

The building itself is actually 138 years old, opening its doors in 1885 as the Studebaker Brothers’ eight-story Lake Front Carriage Repository. Designed by Solon S. Beman, the architect who drew up George Pullman’s company town, its lower four floors had showrooms with high ceilings and large windows, housing as many as two-thousand wagons and buggies at a time that were assembled and repaired on the upper four floors.

Upon its opening, the Chicago Tribune, no stranger to hyperbole, judged the structure a “Magnificent Palace… a lasting ornament as beautiful and as artistic as the Arc de Triomphe or the Column Vendome.” (Seeking more quantifiable brags, boosters also touted the prosaic but unverified claim that the building boasted the largest polished granite columns in the United States.)

But the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company quickly outgrew its showplace. In 1896, it moved into a new ten-story building, also designed by Beman, at what is now numbered 623 South Wabash. (It still stands and is a mixed-use building owned by Columbia College.) The original Michigan Avenue building would have been sold to another company if Charles C. Curtiss hadn’t come up with a better idea.

A Civil War veteran and the son of two-time Chicago mayor James Curtiss, Charles Curtiss had practical experience in both business and the arts. He clerked at Field, Palmer, and Leiter (a forerunner of Marshall Field’s); kept the books for harp-maker Lyon & Healy (still operating today in the West Loop); managed George F. Root and Sons Music Company; and was president of the Manufacturers Piano Company. He was also instrumental in the conception and construction of the Loop’s Weber Music Hall, the first building in Chicago exclusively devoted to studios for musicians.

Curtiss knew artist-only spaces could turn a profit. He also recognized the building’s prime location in Chicago’s developing cultural hub. The Art Institute’s new home was just two blocks to the north and the Auditorium Building next door was home to the Chicago Orchestra. The Athenaeum Building around the corner was already home to many fine artists. And South Wabash was Chicago’s bustling Music Row, lined with music stores and piano showrooms.

When the entrepreneurial Curtiss pitched the concept of the Fine Arts Building to the Studebakers, whom he knew socially, they bought it. According to the late Chicago historian Perry R. Duis, whose writings proved invaluable for this article: “His reputation as a businessman helped convince the Studebakers that cultural entrepreneurship could be profitable.”

The building’s conversion was stunningly swift. Beginning in November 1897, construction crews demolished the ground-floor showrooms, replacing them with two large music halls and several sidewalk-facing stores. They built large studios overlooking Michigan Avenue on the second and third floors, and subdivided the higher floors into a warren of studios for arts, crafts and music, with offices and club rooms, too. The music studios were given extra soundproofing, and throughout, the existing high ceilings and large windows lent themselves to the lighting needs of fine artists. The eighth floor with its turreted roof was lopped off and replaced with an additional three stories. The new top floor—the tenth—featured skylights, sliding doors to accommodate oversized artworks, and a banquet hall that connected to the Auditorium Building’s popular main dining room. Finally, a six-story light well was cut into the center of the building and ornamented according to its new name: the Venetian Court.

When the Fine Arts Building reopened in October 1898, it had been staged to look the part: the lobby was hung with paintings and lined with exhibit cases, while upper hallways were adorned with statuary and ornate benches, softened with palms and ferns. All told, the $600,000 renovation had cost more than twice as much as the building’s original $250,000 construction. But the money had been well spent, both in the eyes of the public and the press. An early review of Studebaker Hall, as the theater was christened, touted it as “the most beautiful music hall ever built.”

Curtiss, the building’s new manager, had moved in during construction to start the leasing process, but he doesn’t seem to have had trouble finding tenants. Many artists had recently been forced out of the Athenaeum Building (the commercial school that owned it had a growing need for space) and simply relocated. Others, dissatisfied with the facilities in buildings like the Masonic Temple, found they could get more room for less money at the Fine Arts Building. Curtiss recruited other desirable tenants, such as noted drama teacher Anna Morgan, whose suite on the eighth floor included a three-room studio and a five-room gymnasium complete with showers and dressing rooms.

Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr, producer, 1904

Music instruction paid most of the freight. The four-story annex, which had been built in 1889, was immediately occupied by Florenz Ziegfeld’s Chicago Musical College (now part of Roosevelt University’s College of Performing Arts). The Sherwood Music School (now part of Columbia College) was founded there in 1895, and nearly a hundred individual teachers also moved in. By 1901, more than ten-thousand students were taking music lessons at the Fine Arts Building.

In short, the building was a hit. In its first few years, artists and crafters of every kind flocked there: actors, carvers, decorators, dramatists, etchers, illustrators, metalsmiths, musicians, painters, publishers, sculptors and writers. (Not to mention the odd elocution teacher.) Commerce quickly took root, too, with small retail shops offering everything from books, prints, and pictures, to linens and lace, to antiques, furniture and pianos.

But it was the best-known artists who put the building on the map culturally. Notable tenants included Chicago’s leading portrait painter, Ralph Clarkson; landscape artist Charles Francis Browne; muralist Oliver Dennett Grover; sculptor Lorado Taft; and cartoonist John T. McCutcheon (who would eventually win a Pulitzer Prize in 1932). William W. Denslow, who illustrated L. Frank Baum’s “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” (1900) worked next to Ralph Fletcher Seymour, who published Baum and would eventually also publish Henry Blake Fuller’s “Bertram Cope’s Year” (1919), now regarded as one of the first American gay novels. Fuller, already the author of the then-controversial Chicago classic “The Cliff-Dwellers” (1893), was a frequent visitor to the building and captured the scene on the tenth floor, where many of the most prominent artists had their studios, in his novella collection “Under the Skylights” (1901).

But the building’s artistic output was not limited to fine and high art. By 1903, twenty editorial publications, many of them mainstream, had offices in the building. Blanche Ostertag arrived from St. Louis to begin her outstanding career as a decorative artist, and German-born commercial artists Frank X. and Joseph C. Leyendecker, the “illustrator twins,” had a three-year residency. The Leyendeckers left for New York City in 1901, but not before supervising the creation of eight Art Nouveau panels on the tenth floor. These paintings—mostly classical figures with a fair number of nudes—caused some members of the Chicago Woman’s Club to gasp and clutch their lorgnettes when they were first unveiled. Modern visitors to the building can still see the scandalous works for themselves.

(As a side note, in 1905, J. C. Leyendecker, now known to have been gay, drew the advertising icon Arrow Collar Man based in part on his partner, Charles Beach. Over the ensuing decades, this fictional pin-up grew so popular nationally that he even received fan mail.)

Less-remembered artists who worked at the Fine Arts Building include the colorful Lou Wall Moore, or “Princess Lou,” a socialite, sculptor and scandalous dancer well worth a Google search; sculptor Alice Cooper; and miniaturist Magda Heuermann.

Any chronicle of a historical art scene risks devolving into a list of names, and yet the names are necessary; they are also necessarily incomplete, a mere fraction of the hundreds who started it and the thousands who would follow. There were other artists’ enclaves already in existence around Chicago—notably, the Tree Studios north of the river—but the Fine Arts Building’s choice location and sheer size gave it a gravity with which no other space could compete.

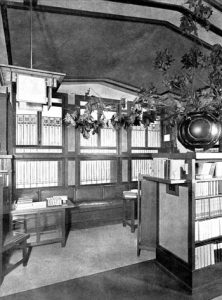

The Fine Arts Building studio of sculptor Lorado Taft, ca. 1910, from “The Book of the Fine Arts Building”

Community in the building formed organically as artists visited each other’s studios or stopped to chat in the halls. The tenth floor, the most prestigious address within the building (the New York Evening Post called it “Chicago’s Parnassus”), became the home to the “Little Room” club, which Elia W. Peattie described in “The Book of the Fine Arts Building” (1911) as an “insouciant, vagrant academy of folk ‘who do things’ in a literary or artistic way.” (The group had been meeting since 1892 and took its name from a Madeline Yale Wynne short story about a room that appears and disappears by magic.) Its impressive membership list included reformer Jane Addams, humorist George Ade, novelist Henry Blake Fuller, architect Hugh M. G. Garden, novelist Hamlin Garland, cartoonist John T. McCutcheon, novelist George Barr McCutcheon (John’s brother), poet Harriet Monroe, drama teacher Anna Morgan, architects Allen B. and Irving K. Pond, illustrator and publisher Ralph Fletcher Seymour, society architect Howard Van Doren Shaw, sculptor Lorado Taft, progressive writer Edith Franklin Wyatt—and even Frank Lloyd Wright, who briefly occupied a studio of his own.

The Little Roomers gathered in Ralph Clarkson’s studio to sip afternoon tea and stage evening performances, discussing issues of the day and indulging a sense of artistic play. (Fuller’s “Under the Skylights” included a blatantly satirical portrait of Hamlin Garland in “The Downfall of Abner Joyce,” painting him as a high-minded populist seduced by sophisticated Chicago society. Garland laughed it off—at least publicly.)

In turn-of-the-century America, civic organizations grew like dandelions, and the Fine Arts Building’s gathering spaces were used by countless clubs, societies and charities—many of them headquartered in the building—from the very start. Between Studebaker Hall and Music Hall on the ground floor, and Assembly Hall (now Curtiss Hall) on the tenth floor, not to mention the individual studios, there were options to suit every size of gathering.

Clarkson pressured civic leaders into creating the Municipal Art League, which fostered art appreciation among city dwellers, and its sister organization, the Chicago Public School Art Society. Almost two decades later, in 1916, the Arts Club of Chicago was founded in response to the stodginess of the Art Institute; taking up residence in the Annex, it promptly sponsored an exhibition of work by “artistic anarchists.” The Chicago Literary Club, the Caxton Club, the Chicago Kindergarten Association, the Amateur Musical Club, the Alliance Française, the Theatre Française, the Young Fortnightly, the College Club, the Wednesday Club and the Thursday Club are just a few of the arts and social clubs that called the Fine Arts Building home.

It is also a notable site for women’s history, both in the arts and in politics. “Here, too, meets the Fortnightly, the oldest of the women’s social and literary societies in Chicago—an organization of Brahmin caste, with a high reputation for its literary product,” wrote Peattie, describing the high-toned cultural and self-improvement association that had been founded in 1873. Notable for early members such as Jane Addams, Bertha Potter and Harriet Monroe, the Fortnightly moved into the Fine Arts Building and remained there until relocating to a Gold Coast mansion in 1922.

The Cordon Club was founded there, after the Cliff Dwellers Club scorned sculptor Nellie Walker’s request to add a women’s division. By the time of the Cordon Club’s first meeting in 1915, membership had been capped at four hundred with a lengthy waiting list and the group met on the eighth floor behind two massive doors beautifully carved by Walker herself. The social club was notable for the fact the socialites were balanced or even outnumbered by professional women. Addams, Morgan and Monroe graced the roster of this club, too—the building must have felt like a second home to them.

Suffragettes Miss Belle Squire, Mrs. George W. Trout, Miss S. Grace Nichols, and Miss Ella S. Stewart standing in front of the Studebaker Theater, later the Fine Arts Building, at 410 South Michigan Avenue in the Loop.

The Fortnightly and Cordon members may have largely left politics and religion outside their doors, but many other organizations did not. The Fine Arts Building would become a hub for women’s groups both on the rearguard (the Colonial Dames, the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Catholic Women’s League) and in the vanguard (the progressive Chicago Woman’s Club and the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association).

The building was also at the center of a burgeoning arts and crafts movement, particularly in book art and bookbinding, the latter an activity encouraged for young women. Ralph Fletcher Seymour produced high-quality limited editions of illustrated books. The bibliophiles at the Caxton Club published limited-edition volumes in the Arts and Crafts style. Other book artists included W. Irving Way, whose studio specialized in hand-illuminated books, bookbinder Gertrude Stiles, the Golden Bindery and the Rose Bindery, where Mrs. Hobart C. Chatfield-Taylor trained young women to make fine-leather book bindings.

Crafts, whether made in the Fine Arts Building or elsewhere in Chicago or across the sea, were sold in wild profusion. In addition to the bookbinders, silversmiths, and photographers, there were shops selling cushions, table covers, screens, decorated china, and copper lamps and lighting fixtures. The Norwegian Shop and the Irish Shop sold transatlantic imports. At the Wilro Shop, Minnie and Rose Dolese sold Swedish weavings and decorated leather card cases, belts, pocketbooks and other accessories. The Kalo Shop sold burnt and embroidered leather goods before turning to the hand-wrought silver tableware and jewelry for which it’s remembered today. At the T. C. Shop, Emery W. Todd and Clemencia C. Cosio made silver serving, dining and flatware. The unfortunately named Swastika Shop offered handmade lighting devices, silver bowls and tableware, jewelry, and old copper, brass and silver. Pratt Studio set stones for the wearer.

As the crafters evolved from single-purpose shops to multicraft cooperatives, they staged joint exhibitions before forming, in 1910, the Artists’ Guild, a five-room co-op store on the fifth floor. A year later, with 128 members, they opened the Fine Arts Shops. Then in 1915, they took over the Annex.

The activity in the Fine Arts Building’s early decades beggars the modern imagination. Isadora Duncan danced on the stage of the Studebaker. Society people took tea at seventh-floor Browne’s Bookstore, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright—who also designed the fifth-floor Thurber Art Galleries a few years later. Browne’s was the brainchild of Francis Fisher Browne, editor of the conservative literary journal, The Dial, which was published on the same floor. Harriet Monroe founded Poetry there (putting out “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” T. S. Eliot’s first professionally published poem in 1915) and Margaret Anderson founded The Little Review there, too (serializing James Joyce’s “Ulysses” beginning in 1915). The Chicago Kindergarten Institute opened the Children’s Book Store, one of the first bookstores catering exclusively to kids. The Marx Brothers brought their vaudeville act to the stage of the Studebaker.

As Chicago architect David Swan put it in his introduction to the facsimile edition of “The Book of the Fine Arts Building” (1911; 2008), “For Charles Curtiss, the completion of the Fine Arts Building was the culmination of a fifteen-year dream to create the ideal conditions for centralizing the artistic, social and literary concerns of the city into a single building… As was noted just a year after the Fine Arts Building had opened, Curtiss had been instrumental in assembling under the roof of the Fine Arts Building ‘all that is best of the best side of Chicago life.’”

But the golden years were about to run out.

Act One. The Golden Age: A Building Reborn

Interlude. Footnote in the Footlights: Samuel Insull and Gladys Wallis

Act Two. Depression and Decline: Charles Curtiss Dies

Interlude. Curtains Rise and Fall: The Fine Arts Building’s Theaters

Act Three. Shabby Grandeur: Tom Graham to the Rescue

Interlude. Death in the Afternoon: “No, Paul! God, No, Paul!”